Applying management principles to Rare Diseases: How a dad navigated his daughter through Pompe Disease and paved the way for many.

- Sudha Bhattacharya

- Mar 2

- 38 min read

Updated: Mar 4

Long before the professional management degree became a passport to success, the world of commerce was managed (perhaps better) by intuitive managers. With a macro vision of the world around them, and a micro vision of their own immediate circumstances, an intuitive manger has the innate talent to determine the best strategy for attaining their goals. Once a decision is taken, there is no wavering, no second thoughts; just a single-minded pursuit to get the job done. Such were the attributes young Prasanna possessed even as a boy.

Prasanna’s family hails from the Dharwad-Hubli region of north Karnataka. His father was a college professor and the general inclination of the family was towards learning and education. But Prasanna was a very hands-on kid. He knew he would never become a teacher. Rather, he was excited by the thought of going into farming, or setting up a business. But he went along with the family tradition and entered college. His strategy was to study just enough to clear exams with decent marks, giving his father a pleasant surprise each time. The one time he actually enjoyed his studies was when he enrolled for the MBA course. Business management came to him naturally and he passed with a gold medal.

While still in the third semester of his MBA course, Prasanna was selected by the pharma company Cipla to work for them in a project in Mumbai. The work involved promoting Cipla’s new drugs so that doctors could prescribe it to their patients. In effect it meant running endlessly behind doctors, a task Prasanna did not enjoy as he felt he could hone his marketing skills better with the consumer industry. He managed to chase doctors for just three days before quitting Cipla. Little did he know what Providence had in store for him. Chasing Doctors was to be the mission of his life just a few years down the line.

Prasanna realized his interest lay in launching new consumer products, and providing customer services. After working for various companies and spending a few years in Bangalore, Prasanna landed a job with Sony in 1996. It had many pluses, not the least of which was that he was to work in Hubli, his home town. Sony wanted to make inroads into Hubli where their presence was inadequate. Sony’s high-end products were typically more expensive than contemporary brands, and had to be procured from Bangalore. Prasanna took on the challenge by strategically organizing exhibitions of high-end Sony products in Hubli, which gave customers a first-hand experience of the product, and they could directly purchase it without having to travel to Bangalore. The market for Sony products was thus created, and sales started soaring. Having established himself professionally, it was now time to marry and ‘settle down’.

In 1998 Prasanna was betrothed to Sharada, a young science graduate, whose family also hailed from Hubli. Her father too was a teacher. In the safety cocoon of family traditions, the young couple felt secure and blessed.

5th March, 1999

Prasanna and Sharada welcomed their first baby, a beautiful girl, their precious treasure of love, and they named her Nidhi. She was a normal baby at birth, and her arrival was greeted with great excitement and rituals in both families. On the 9th day, however, Prasanna noted something odd in the shape of her ankle. The elders in the family calmed him, as such oddities ironed out gradually with regular massages. The next three months were uneventful until Nidhi came down with pneumonia and diarrhoea. She was also vomiting out the breast feed. The paediatrician was not too worried as Nidhi easily responded to medication.

Baby Nidhi was otherwise growing normally and charming everyone with her smiles and gestures. Prasanna and Sharada, while basking in the delights of watching her grow, had nevertheless, a constant nagging fear of something amiss. At 10 months their little treasure was not crawling like other babies, and the episodes of pneumonia and vomiting, though controlled by medication, kept recurring. Over the next six months Nidhi started to stand up holding on to furniture. She could also take a few steps and walk, although she fell easily. But her milestones were noticeably delayed, and the paediatrician now advised them to consult a neurologist. The CPK levels in her blood were tested and found to be elevated, an indication of an underlying pathology like muscle damage. They were now advised to get specialized treatment from NIMHANS.

2001- Tentative diagnosis

Nidhi was admitted at NIMHANS and the doctors conducted several diagnostic tests, including a muscle biopsy test. Although they could not reach a confirmed diagnosis, their likely verdict was glycogen storage disorder, type II. When translated into simple English it meant that Nidhi had eight to ten years to live out a life of progressive muscle decay until she would collapse under her own body weight. Even breathing would become difficult. Although life expectancy varied among individual patients, the disease was severe and there was no treatment for it.

Processing a harsh reality

Prasanna and Sharada had entered NIMHANS with an open mind. Subconsciously they were prepared for the worst. But this… what the doctor told them in a cool tone was surely worse than the worst. And it seemed so incongruous. How could the doctor be talking about their baby? Their little treasure with the sparkling eyes was, at that moment, soaking in the sights and sounds of this new city. Those eyes did not belong to a withering body. They were raring to explore and own the world.

Prasanna and Sharada exited the hospital in silence. The tempest in their minds had left them dumbstruck. But by the time they reached their hotel room, Prasanna had put on his managerial hat and was charting out the next course of action.

Shared grief can be a powerful cement between two souls. Like any other married couple, Prasanna and Sharada had opposing views on almost every other issue. But when it came to Nidhi their decisions were always unanimous; as though thought by the same mind. They now made some important and practical decisions. Their principle aim at this point was to give Nidhi as ‘normal’ a life as possible, no matter how many years the supreme Almighty had granted to her. Ironically, that meant not revealing the seriousness of her illness to anyone in their close circle. Children are highly perceptive, and pitying glances or escaped sighs are powerful cues. From outward appearance Nidhi seemed like any other baby except for her mobility issues. None in the family suspected anything seriously amiss- so they would just let it remain at that.

They also realized that to help Nidhi they needed to further understand and monitor her rare illness. But they knew so little about it. All they could gather from the NIMHANS trip was that it was a rare disease, of a serious nature, for which there was no treatment. How did it originate? What was the underlying cause? Could they meet others with the same disease? Whom to turn to for advice? With these and similar questions welling up in him Prasanna went to see Nidhi’s neurologist in Hubli. The doctor suggested that Nidhi’s illness could be a genetic disorder, the first doctor to make such a suggestion to them. He advised that they should get Nidhi examined at the human genetics department of Manipal hospital in Bengaluru, which could give them a confirmed diagnosis.

2002- 2004: In search of a confirmed diagnosis Manipal hospital

Frequent trips to Bengaluru would not raise eyebrows in the family, as Prasanna was already making periodic visits to the Sony head office in Bengaluru for his own work. On his next work visit he made an appointment at Manipal hospital and took Nidhi and Sharada along. A genetic test was conducted, but somehow the report never came even after several weeks. Instead, the genetics department referred them to other departments like cardiology, gastroenterology etc. Several hospital visits and tests later, they were none the wiser about Nidhi’s illness. Prasanna realized that something was amiss- perhaps the genetics department had lost Nidhi’s test report. They had gone to Manipal hospital with great hopes of understanding the disease. Unluckily for them, they had to abandon this hope and seek other sources.

JIPMER, Puducherry; Chennai; Mumbai -

It was clear to Sharada and Prasanna that getting a confirmed diagnosis- the first step towards understanding the disease, was going to be a long haul. They had to explore beyond Bengaluru, wherever competent neurologists practised. Prasanna used the motivational tactics he employed for clients on Nidhi as well. The doctor’s visit was made to appear as a side trip in the larger purpose of going out for a family vacation. Driving on highways, which is a nightmare for many, is Prasanna’s passion. So, the three of them drove to Puducherry, Chennai, Mumbai to consult various neurologists…. Alas, everywhere the same tests were conducted, which were not conclusive. Darkness prevailed.

Bengaluru -

By now Nidhi was 5 years old, and going to school. She was a vivacious, outgoing, friendly kid with a lot of friends. All was normal, except that she could not run and jump, and could fall easily. She loved playing outdoors, but due to poor balance she started avoiding larger groups. Rather she would hold the hand of a close friend to play.

In the interim a lot had happened in Prasanna’s career. He had risen the ladder in Sony and several times he had been pressed to move to Bengaluru. Every time he managed to convince the administration to allow him to continue from Hubli as the familiar surroundings and family support were vital for Sharada and Nidhi. Finally in 2002 the pressure to move to Bengaluru became so strong that Prasanna decided to quit Sony. He joined Reliance Industries which enabled him to continue from Hubli. He did so well in his job that here too in a couple of years they insisted that he move to Bengaluru. Thus, in 2004, Prasanna, Sharada and Nidhi moved to Bengaluru. The weather in Bengaluru is not particularly conducive for asthma patients. Nidhi started suffering from frequent bouts of pneumonia. Fortunately, they found a very good paediatrician who took great interest in Nidhi’s overall condition. He strongly advised them to consult Dr. M. L. Kulkarni, a renowned paediatrician with keen interest in rare diseases. Dr. Kulkarni was based in Davengere, which is located about 200 km from Bengaluru. Several other people in Prasanna’s contacts also highly recommended Dr. Kulkarni. Prasanna then decided to give this doctor a serious try.

2005, Davengere: Desperate measures for desperate ends

Prasanna now convinced his boss at Reliance to transfer him to Davengere, and within a year the family moved once again. Dr. Kulkarni examined Nidhi, studied all her reports, and like the other doctors who had treated Nidhi, he too did not give a confirmed diagnosis. He too basically said the same things- it is a long-term disease, with no treatment.

Yet, seeing his body language and the way patients flocked to him, Prasanna felt that he had found the doctor who could help him with a diagnosis.

Although the doctor had nothing further to offer, and did not ask to bring Nidhi again for check-up, Prasanna started visiting his OPD every day. He waited patiently for the OPD to close, when the doctor could have time to glance at him. It was always a brief affair as the doctor would immediately dismiss him. Yet day after day Prasanna would show up at the OPD, as if drawn by an invisible force. Then one day the doctor actually spoke to him. He said, “have I not told you there is nothing to be done. Why, then do you come here every day?” Prasanna replied, “I come here because I know you can help me to get a diagnosis.” The doctor then laid two conditions to help Prasanna- 1. Be prepared to spend money for it; 2. Bring Nidhi for examination whenever required. Prasanna agreed instantly, at which his tapasya was answered.

2007: The diagnosis at last

Dr. Kulkarni sent a team of junior doctors to their house to jot down their entire history. The team visited several times, took extensive notes and prepared a 10-page document, which was discussed in their group meeting. Finally, they collected a blood sample of Nidhi and sent it to Gangaram hospital in New Delhi for enzyme assay, for which Prasanna had to spend a few thousand Rupees. The test came positive for Pompe disease, a rare genetic disorder caused by deficiency of the enzyme alpha-glucosidase. It belongs to the broad category of diseases called Lysosomal Storage Disorders.

What is Pompe disease?

Pompe disease is named after the Dutch pathologist Joannes Pompe who first discovered it in 1932. It is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder, that is, the disease appears when an individual carries both defective copies of a gene coding for the enzyme acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA). The GAA enzyme is needed to break down glycogen when its levels are elevated inside the cell. Defective GAA enzyme leads to accumulation of glycogen to toxic levels in the lysosome. Pompe disease is, therefore, also called Glycogen storage disease type II (GSD-II).

What is glycogen and why is it important? It is a carbohydrate polymer made up of thousands of glucose units. It is made when glucose is in excess (as after a meal), and is stored mainly in the cells of liver and muscle. When food is in short supply or when energy demand is high, glycogen is broken down to release glucose, which provides the energy currency of the cell. There is an intricate balance between glycogen synthesis and breakdown.

What is lysosome and what are lysosomal storage disorders? The lysosome is a special compartment in the cell. As its name suggests, its job is to lyse, or break down, material that is brought into its space. This material could be foreign particles like viruses, or it could be a variety of cellular components. Glycogen is broken down into glucose units in the lysosome by the action of GAA enzyme. In Pompe disease this enzyme is inactive, leading to abnormal levels of glycogen accumulating in the lysosomes. Like glycogen, there are many other cellular components that are brought into the lysosome for breakdown and recycling. Each component is broken down by a specific enzyme coded by its corresponding gene. Mutations in any of these genes can cause serious disease by toxic accumulation of excess cellular component. Since the accumulation occurs in the lysosome these disorders are collectively called lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs). Pompe disease was the first recorded LSD, and there are more than fifty currently known LSDs.

Symptoms of Pompe disease

Accumulation of glycogen in the lysosomes of muscle cells leads to severe and progressive tissue damage, especially in the limbs, heart and diaphragm. The liver and nervous system may also be affected.

Since the disease originates due to deficiency of GAA enzyme, symptoms and disease severity vary depending on residual levels of GAA in the body, as also on the type of mutation. Accordingly, the disease has been classified into two broad categories -

Early onset (infantile form) is more severe, involving multiple organs. Symptoms appear in the first few months, with feeding problems, poor weight gain, breathing trouble, enlarged heart, floppiness etc. Life expectancy may be less than a year without treatment.

Late onset (juvenile/adult) is due to partial GAA deficiency and is less severe. Symptoms begin in childhood or adulthood, and involve muscle weakness and consequent disability. Here too, multiple organs may be involved, leading to respiratory problems, hearing loss, nervous system abnormalities, scoliosis, loss of bone mass, as well as gastrointestinal and urinary tract symptoms.

There is a third category which would better describe Nidhi’s progression. This is the early onset type, but without/or less severe cardiomyopathy, delayed motor skills and involvement of multiple organs as in the late onset disease, but at an earlier age.

2007: Could a treatment be round the corner

Along with the diagnosis, what Dr. Kulkarni told Sharada and Prasanna was sheer music to their ears. A drug was being tested for this disease abroad, and the results were positive. He advised them to go to Delhi and meet Dr. I C Verma at Gangaram hospital. In India no one knew more about this rare disease than Dr. Verma, and he could guide them about the way forward.

A slip between the cup and the lip

With Prasanna’s managerial acumen he could have organized this trip to Delhi the very next day, but destiny’s plans were otherwise. By now Nidhi was eight years old and the larger family, who still had no clue about Nidhi’s disease, had been heavily pressurizing them for a second baby. Sharada was now pregnant with their second baby. Her gynaecologist at Davengere became alert when she learned about Nidhi’s diagnosis. The network of doctors in Davengere was much stronger than anything in metro cities, which Prasanna noted with great satisfaction. The doctors were all talking to one another. Their gynaecologist recommended them to go to Bengaluru for a prenatal test for Pompe disease. This was done using cells from the amniotic fluid (possibly by testing for the enzyme activity), but Prasanna is not sure how exactly it was done. The test showed that the fetus was positive for Pompe disease. The cruel throw of dice had worked against them yet again, and they had to terminate the pregnancy. To this day the pain of having to bury the unborn foetus has not left Sharada and Prasanna. Added to this is the chilling doubt- what if the test report was incorrect?

September 2007: A greater tragedy unfolds soon after

Prasanna and Sharada are inherently devout persons, and find immense solace at the feet of God. They visit temples regularly. After the terminated pregnancy, Prasanna organized a trip for the three of them to worship at the Jyotirlinga temple in Srisailem. They needed His blessings to grant them the strength to wade through these testing times. God decided to put them further to the test.

At the temple a strange thing happened. Like her parents, Nidhi too liked to pray at the temple and followed the rituals. This time, however, when she reached the lingam, she suddenly turned sharply to the right and refused to pray; as though she had a premonition that prayers were not going to be answered this time.

When they returned to Davengere Nidhi came down with acute pneumonia. She was rushed to the ICU, where she was immediately placed on ventilator. The doctors in Davengere were inexperienced about ventilator operation, and Nidhi’s condition did not stabilize. After one week in the ICU the doctors were giving up hope. Prasanna immediately swung into action and arranged for an ambulance with ICU facility, and moved Nidhi to Manipal hospital in Bengaluru. Realizing that the medical facilities in Davengere were now going to be inadequate for Nidhi, he decided to move to Bengaluru. On the way, in the ambulance itself, he talked to his manager and got himself transferred from Davengere. Simultaneously he called his brother-in-law to pack up their stuff and transport it to Bengaluru. Such lightning decisions are Prasanna’s trade mark, and when it comes to Nidhi, the couple never have a difference of opinion.

By the time the ambulance had covered the bumpy ride from Davengere to Bengaluru, Nidhi’s chest cleared as the accumulated mucus was released, and she recovered. But after 24 hours in the ICU as she lay static, the congestion again built up. Here too, the doctors were not hopeful of recovery. Sharada and Prasanna then purchased a ventilator and decided to take Nidhi home on it. The doctors at Manipal were very cooperative and trained Sharada on all the intricate ventilator operations so that when they moved home Sharada could take complete charge of Nidhi. They had strategically rented a house right next to the hospital so that in an emergency they could shift Nidhi without delay.

Keeping Nidhi positively motivated in this new normal

Thus far Nidhi had been contending largely with mobility issues which did not require critical care. She had adjusted to the low mobility life style. The serious respiratory complications that befell her now were dampening the child’s spirits. A positive state of mind is half the battle won, and Sharada and Prasanna took all measures to keep Nidhi motivated. There was no point in denying that there was a problem, but they assured her that treatments are there and she will soon be better. Nidhi’s doctors also really helped in this regard and kept her positive.

The real concern was their families. By now, it was obvious to all that Nidhi had a serious illness. This fact could be easily conveyed to Nidhi by one or the other family member through their gestures and expressions. Nidhi was acutely sensitive to such cues. In fact, during this phase, when Nidhi was in Manipal hospital, one day Prasanna had not shaved as he had taken a month’s leave from his office. This immediately raised doubts in Nidhi’s mind and she questioned her dad. You say I am OK. Then why have you not shaved and gone to office? From the next day Prasanna would be in his business clothes, and go to see Nidhi only in the morning and evening; spending the rest of the day in the hospital. She now felt reassured that things were normal and became cheerful. To keep this fragile narrative from crashing they had no choice but to maintain a certain aloofness with the family and discourage long meetings with Nidhi. In addition, they were saved the bizarre advice from well-wishers- leave it to God; why fight against Nature; and, confident that the fault must lie with Sharada, advising Prasanna to go for second marriage.

Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT), a drug at last for Pompe disease

While Sharada was with Nidhi literally round the clock, Prasanna started scouting for information about the Pompe drug that Dr. Kulkarni had mentioned. Internet connectivity those days was far inferior than today; but they could access a lot of information through Veena, a close friend of Sharada residing in the U.S. Veena told them about the International Pompe Association in the Netherlands, and put them in touch with Dr. Priya Kishnani, originally from Mumbai, now working in Duke University. She is a world-renowned expert in Pompe disease and got immediately interested in Nidhi, being the first officially-diagnosed Pompe patient from India. Dr. Kishnani got in touch with Genzyme, the company that was manufacturing and marketing the ERT drug. Genzyme was looking to expand their international footprint and were planning to start operations in India. Acknowledging that the high cost of drug would put it out of reach for most patients in India, the company had the vision to initiate an International charitable access program whereby the drug would be supplied free of cost to selected patients. However, the inclusion criterion for the charitable program was babies less than 2 years of age, which immediately disqualified Nidhi from the program.

By then Genzyme opened their India office and appointed their first employee, Mr. Sandeep Sahani. Prasanna got in touch with him, and sent him Nidhi’s entire medical records.

March 2008

The ERT drug was now accessible in India. All it needed was a few crore Rupees a year. Prasanna with his salaried job would never have that kind of money. Every day he kicked himself for not being able to do enough for his daughter. After all, there were people in India making that kind of money. He would have to take some drastic steps. He decided to quit his job and start a business, any business, that could give him high returns rapidly.

28th March, 2008

That date is etched in Prasanna’s memory, for that was the day his God smiled at him. Prasanna received a phone call from Sandeep Sahani informing him that Genzyme had approved Nidhi for the charitable access program, as a special case! Prasanna tore off his resignation letter. There was celebration at home.

What is Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT)

Since Pompe disease, and most other LSDs, are caused by deficiency of a single enzyme/ protein, it seems straightforward to expect that if the active enzyme could be supplied to the lysosome, the normal physiological process would be restored. However, normally the active enzyme is made inside the cell and has only to move to another cellular compartment, the lysosome. For therapy we would be providing the enzyme from outside. Would it then enter the lysosome? It turns out Nature has already done the job for us. In the cell, a small amount of the enzyme does leak out of the cell and is again taken back into the lysosome. To be allowed re-entry, however, the enzyme needs the right identification tag, which is in the form of a sugar called mannose-6-phosphate (M6P). Thus, while designing the artificially produced, active enzyme for ERT, care is taken to provide it with a prominent M6P tag. Another encouraging factor that spurred the development of ERT was the fact that parents with one defective gene copy are symptom-free. Thus, introducing even small amounts of active enzyme could ameliorate some of the disease symptoms.

The ERT drug composed of suitably modified GAA enzyme goes by the name alglucosidase alfa (Lumizyme or Myozyme). It was marketed by Genzyme, later acquired by Sanofi. It has been game-changing for Pompe disease. It has improved clinical outcomes and prolonged survival in patients. The best outcomes are obtained when the drug is administered very early, for which newborn screening is essential. Practical issues which confound the use of ERT are its very high cost, and need for i.v. infusion every few weeks.

July, 2008

Nidhi received her first dose of the ERT drug administered bi-weekly intravenously. Within a few months the drug began to show its effect. Nidhi could now get up, stand and walk a few steps on her own. Slowly they could wean her away from the ventilator during the day, although it was continued at night.

2009: Back to school

Nidhi had always enjoyed her studies. Even though she was on ventilator she was keeping up with her studies with the help of her mom. Knowing how much she enjoyed going to school and being with other kids, the Shirols now started looking for a school that would admit Nidhi. In terms of intellectual abilities, she was a sharp kid, but physically she needed special care. Her saliva secretion had to be removed by suction at regular intervals, and she needed help to use the washroom. After being refused by several schools, Nidhi finally gained admission to class IV in a school at the outskirts of Bengaluru, with the condition that Sharada would stay outside the classroom for the entire day. That was the easy part. The tough part came when a few parents started raising concerns that Nidhi’s disease could be contagious and affect their children. They were finally convinced after educating them about Pompe disease and its genetic origin. Nidhi was once again with friends of her age. In spite of her physical disability she was happily mixing with kids in her class.

Three years later

A good measure of normalcy had returned to Nidhi’s life, thanks to the ERT drug. She was now in class VII and performing very well. Alas, the good times seemed to be coming to an end as the effect of the drug began to wear off. Nidhi began to slump rapidly, and could not walk any more. Her doctor suspected, rightly, that her immune system might be making antibodies against the drug and inactivating it. Nidhi’s blood sample was shipped in dry ice to USA for antibody testing against alpha glucosidase. The results showed very high levels of antibodies against the enzyme. It meant that the only way to save Nidhi was to suppress her immune system, which is otherwise so essential for the body. Nidhi received immuno- suppressive therapy to stop the production of antibodies against the ERT drug. The treatment needs utmost care as it leaves the individual vulnerable to infections. Once again Nidhi had to discontinue her school. The Shirols, who had earlier shifted residence close to Nidhi’s school, now shifted close to the hospital as Nidhi had to be taken there every 3-6 days for i.v. injections of the immunosuppressive drug. The treatment cost them 12-13 lakh Rupees. It started showing good results and Nidhi began to improve. As Nidhi was immuno-compromised they had to maintain ultra clean conditions at home and take precautions like wearing mask and gloves. Nidhi’s room was like a mini-ICU. It was all worth it as Nidhi’s antibody levels dropped and she began to improve rapidly and regained her strength. Although she used the ventilator at night, she no longer needed it during the day time. However, her walking ability did not get restored, and she became wheel-chair bound.

2012: Clouds of despair once again

Although Nidhi had to discontinue her school for a year and a half, she had continued studies at home and had cleared all her exams. This enabled her to rejoin school once the ERT drug became effective again. But another trouble was now brewing up. Nidhi was losing the ability to sit straight; her head began to droop on her shoulders. She had started developing scoliosis (or, bent spine)! It was necessary to control it rapidly through surgical correction; or else she could soon be bed-bound. A rude shock awaited them when they visited the surgeon. They were told that surgery was not possible for a child on ventilator support. Once again, they were immersed in gloom. Once again, they were to emerge victorious.

At this time, Prasanna got a chance to visit The Netherlands, which being the birthplace of Pompe, has the most experienced doctors of Pompe disease in the world. Here, the doctors offered to perform surgery on Nidhi free of cost, but the Shirols would have to bear the expense of travel and stay. Apart from the cost, the logistics of handling everything in a foreign country, especially if an emergency arose, did not give Prasanna the confidence to take on this project. But it helped him to understand that surgery was, indeed, possible in Nidhi’s condition, and he decided to pursue the doctors at Manipal. Although the surgery by itself was possible, the surgeon was reluctant because he was not confident about adequate support from others in the team, especially anaesthesiologist. None of them had any knowledge or experience with Pompe disease which increased the risks for Nidhi, as she was on partial ventilator support, and on immune-suppressive treatment. A year went by, during which Prasanna kept pursuing all the experts- anaesthesiologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist, general medicine, who would be required to assist the surgeon. They started reading about Pompe disease and became familiar with the precautions necessary to avoid co-morbidities. The team now took on the challenge and the surgery was performed. It was highly successful, so much so, that on the fourth day itself Nidhi was discharged from the hospital. Her house was, anyway, a mini-ICU!

2013- 2016: Nidhi, the teenage girl with an iron will

Nidhi recovered very well after the surgery and began to exude the glow of early teens. Life began to fall back on track once again. She had always been serious about her studies and she now started picking up the threads. She joined open school directly in class 10 and started studying at home with the help of Sharada and a neighbourhood aunt who was a high school teacher. By now Nidhi was in the media, and many people were ready to lend their support.

In 2014 Nidhi completed her class 10 and joined pre university (Class 11-12) with specialization in commerce. She enrolled in a regular college and attended classes physically. Unfortunately, she could not make too many friends as she was on wheelchair. She lacked exposure to the latest teenage fads, and couldn’t converse freely with others as she was on ventilator. Her muscles were getting weaker slowly. She could no longer lift her book or turn the pages. All of that was done by Sharada as she was constantly by Nidhi’s side. In spite of huge constraints, Nidhi prepared for her Board exams with a very positive frame of mind. Her parents made sure she was never morose. They went for regular family outings, watching movies, shopping and more. Nidhi completed class 12 in 2016 with a brilliant performance, scoring over 95% marks in two subjects. It was now time to enter college.

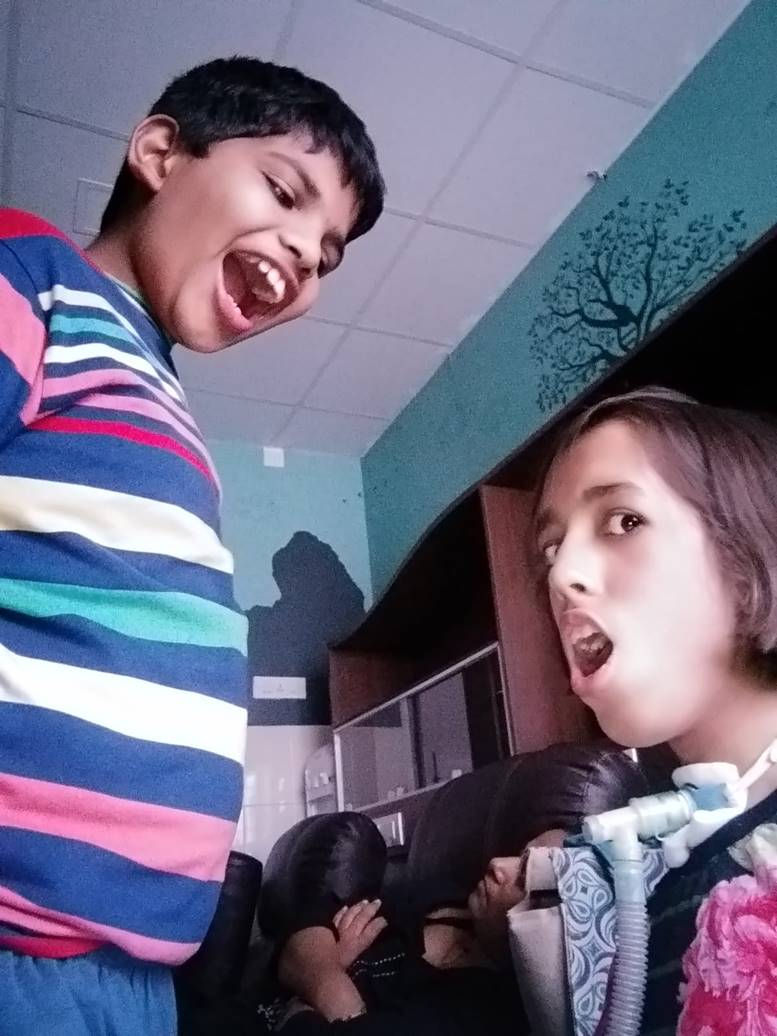

2017: Flying high in college

Although Nidhi was on wheelchair and had to use the ventilator during the day as well, her undergraduate college class received her with a warm welcome and she spent some of the happiest moments of her life there. She found a set of extremely nice class mates who took full charge of her during college hours. All this while, Sharada had been Nidhi’s shadow, being available for her every need. Now it was the friends feeding Nidhi at lunch time, plugging her ventilator to the mains when the battery charge was low, and taking care of her in every way. For the first time she was living like any other teenager, going out with friends to eat pani puri, watch movies, do random shopping… all on her electric wheelchair, with ventilator in position!

September 2017: Alas, too good to last

Nidhi deserved every bit of the good time she was having. She could well have waded through college riding the same wave, and how one wishes the storm to come had never happened.

It was ‘Ethnic Day’ in college. Everyone, including Nidhi, was dressed in ethnic attire. Students had put together a fun-filled cultural program show-casing the songs, dances, food etc. of every ethnicity. Nidhi reached college at 9.30 in the morning and was enjoying all the programs immensely. At 2pm, Sharada arrived to pick her up to go home. Nidhi messaged her to wait at the college gate, as she was coming out. Since she was on wheelchair, she had to take a longer path to reach the gate. Meanwhile, her friends took the shortcut and stood waiting for her outside. In those few moments that she was alone, Nidhi’s world came crashing down without a sound. Her ventilator battery was completely discharged. She had not noticed the warning beep of the battery in all the loud music playing continuously. The ventilator needed to be plugged to the mains immediately, but the friends who knew how to handle this were not around. Nidhi frantically called a teacher passing by to help. By the time they reached a classroom to connect the ventilator, the battery was dead and was taking time to reboot. Nidhi kept signalling to the teacher to pull out her tracheal tube so that she could push her lungs to breathe mechanically. But the teacher did not understand her. In a few moments Nidhi suffered a heart attack and went unconscious.

There was complete panic. Teachers immediately called the ambulance but they did not have Sharada’s contact number handy to inform her. By the time Sharada entered the scene, a precious fifteen minutes had elapsed. The ambulance had not yet arrived. There was no time to waste. Sharada began running on the road towards the hospital with Nidhi lying collapsed on the wheelchair and hundreds of students running along. Midway to the hospital the ambulance caught up with them. They gave an electric shock to revive the heart. Nidhi began breathing again, but the brain had suffered damage and she entered into a coma.

Back to Manipal hospital: Let her go

Nidhi was shifted to Manipal hospital in the comatose condition. The doctors advised them to wait for a week. She might emerge out of it. Ten days elapsed but she remained in coma. The brain had suffered damage due to hypoxia (low oxygen) and nothing could be done to reverse it. The doctors at Manipal were very familiar with Nidhi, having treated her from the start. This time they knew she couldn’t come back. Even if she did revive, she would be a mere vegetable with no memories or recognition. They advised the Shirols to accept the reality and let her go. But for the parents this was unthinkable. Their child was not brain dead. She was breathing. Her organs were functioning. Where was the question of letting go of their priceless treasure. They raised money to pay for the ICU bills. Within 30 days they had already paid Rs. 25 lakhs. Now there was pressure from the hospital to remove Nidhi from the ICU as the bed was needed for other critical patients.

Back home through a circuitous route

Nidhi’s home was a semi-ICU, so they could have shifted her home directly. But this time Sharada was not so confident. Nidhi was expressionless. There was no way to understand her needs. The care-giving level had changed and Sharada needed time to adjust. By now, Prasanna was working hard to raise awareness amongst doctors and patients about rare diseases, and due to his advocacy work he had become a familiar figure in hospitals. The Director of the government-run Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health agreed to provide a hospital bed for Nidhi at almost zero cost, but without full-time nursing care. They hired a private nurse, which was very expensive. After 45 days Sharada was still not confident to handle Nidhi alone at home. She needed more time in a hospital setting. They now moved to Elanka Ayurvedic hospital where nursing care was inexpensive. This hospital was in a beautiful resort-like setting. In a calmer state of mind, Sharada slowly learnt to manage Nidhi completely on her own. They spent a good nine months in this hospital. Nidhi was undergoing ayurvedic treatment here and was beginning to respond. It was now time to move back home.

2018-2023: At home, the journey to eternal peace

The Shirols were encouraged by Nidhi’s positive response to the ayurvedic treatment. They consulted more ayurveda specialists and the treatment continued along with the ERT. She was now moving her lips and gazing at objects. She would open her eyes in response to a sound, or when her name was called. Even though she was lying motionless, her face had a radiant glow. All her vital parameters were normal. Liver was functioning well, and there was no cardiomyopathy, a common co-morbidity in Pompe disease. The Shirols had much to thank their God for.

Verbal communication is never a necessity to unite with someone you truly love. Sharada and Prasanna knew that Nidhi could perceive their presence, and that, by itself, was their trophy. When Prasanna returned home in the evening and called out her name, she would open her eyes and turn her gaze towards him. It filled his heart with sheer joy.

Two years went by. Nidhi was slowly and steadily improving. And then, all of a sudden, she again became unresponsive. She was no longer reacting to sounds or movements around her. An MRI scan showed fluid accumulation in her brain, for which surgery was required. The doctors’ response was predictable. They advised the Shirols not to torture their daughter any more. Just let her go.

But the ayurvedic doctors were hopeful. They prescribed a particular ‘lepa’- a paste of a powder in oil, which was to be applied all over her shaven scalp, starting with the forehead. By the 3rd day Nidhi began to show some response. She steadily improved, and by the 28th day her responses returned. She started opening her eyes to sounds. When they played her favourite songs, her response appeared slightly more eager. Around this time Prasanna had to travel abroad for eight days. When he returned, and called out her name, the speed with which she opened her eyes and looked at him convinced them that she was recovering.

Nidhi had now stabilized. She was on ventilator and ERT, in addition to the ayurvedic drugs. The next three years passed without incidence, till a severe medical emergency arose once again.

November 4, 2023

Prasanna was invited to deliver a TED talk and was in Pune for recording the talk. At 3am he got a frantic call from Sharada. Nidhi was bleeding profusely from the tracheal tube and had already lost about a litre of blood. Prasanna immediately called Dr. Bhaskar, their neighbour and close friend for help. Nidhi was rushed to Manipal hospital where her bleeding was controlled and she stabilized. On his return to Bengaluru Prasanna arranged for a room in the hospital where Nidhi could be transferred once she was out of ICU.

November 9, 2023: When the rare disease community of India lost an icon

Nidhi was to be shifted out of ICU. At 7am Prasanna came home to collect Nidhi’s suction machine and other stuff. Just at that time another severe bleeding episode occurred while she was still in the ICU. Before Prasanna could get back to the hospital Nidhi had already breathed her last. The first officially diagnosed Pompe disease patient of India, having fought the disease for 24 years with exemplary courage, had finally succumbed.

Nidhi had shown the path of strength and resilience when the dice were stacked high against her. She had been a symbol of hope to the entire rare disease community of India. Her passing was not just a loss for the Shirols, it left the whole community shattered.

The Shirols: A picture of calm composure in the face of deep loss

Sharada had nursed Nidhi like a porcelain doll, shielding her from the slightest scratch. Now that she was gone there was quiet acceptance before the will of God. Nidhi’s organs were donated to NIMHANS, after which she was taken to their home town where Prasanna owns a piece of land. Nidhi lies buried there, which is now a scared site. They plan to construct a small temple there for regular puja. For now, they have planted the auspicious Banni (or Shami) tree at the site. In Karnataka the leaves of this tree are gifted to one’s dear ones during the festival of Vijayadashami as a symbol of love and respect that outweighs gold. Its presence at the site where Nidhi lies will be a reminder to all that suffering can be overcome by love and devotion for which wealth is inadequate.

Present and future therapies for Pompe disease: ERT and more

Limitations of ERT and future directions: As with most therapies, ERT has important limitations which are being addressed in the next-generation versions.

Antibodies against the enzyme- Apart from a range of side effects, an important factor that limits the use of ERT is the development of antibody response to the administered enzyme which can make the treatment ineffective. Immune suppression and immunomodulation is carried out using agents like methotrexate, rapamycin, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs) etc. Immunomodulation is most effective when given to patients before ERT (prophylactic approach) rather than after they have developed antibodies (therapeutic approach). Prophylactic treatment requires less intensive, and shorter duration of immune suppression. It is also more effective to generate immune tolerance in patients. Future strategies to improve ERT include development of targeted immune tolerance to ERT enzyme to prevent further antibody response.

Poor uptake of GAA by the lysosome- A second-generation Neo- GAA enzyme has been made by Sanofi in which the amount of M6P has been increased to improve enzyme uptake by the lysosome. Along similar lines, Amicus Therapeutics has prepared a combination drug with the enzyme along with a small molecule pharmacological chaperone (Miglustat) meant to ensure that the injected enzyme remains in an active and stable state in the body.

Therapies based on small molecule drugs

These drugs are generally less toxic, immunogenic, and mutagenic compared to gene therapy and enzyme therapy approaches. They also have the advantage of being able to reach the brain in cases of central nervous system impairment. They can work in various ways, of which molecules that can reduce the concentration of substrate (in this case, glycogen) can be useful for Pompe disease. Reducing substrate concentration could be achieved by inhibiting its synthesis, or by sequestering it to reduce its entry into the lysosome. Such molecules have been approved for some of the LSDs, though not yet for Pompe. Possible limitation of some of these drugs could be their non-specific effects on other pathways, or efficacy only at very high doses.

Another class of small molecule drugs that could benefit patients of Pompe disease are those that modulate autophagy, the process the cell uses to remove waste and renew itself. Skeletal muscles require efficient autophagy because mature muscle fibers are non-dividing cells and cannot dilute out any aberrant proteins and cellular components through cell division. Using drugs to optimize autophagy in muscle could be helpful for Pompe disease by preventing muscle wasting.

Cell and gene-based therapies

Transplantation of bone marrow or mesenchymal stem cells- Healthy transplanted cells from normal donors can secrete the normal enzyme (GAA in this case), which can be taken up by neighbouring diseased cells, and transported to their lysosomes via the M6P tag mechanism. This method is called cross-correction.

Gene therapies- Pompe disease and most other LSDs are caused due to single gene defects, making them amenable for gene therapies. Delivery of a normal copy of the gene using adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based vectors has shown encouraging results in animal studies. Approval has been granted for several human clinical trials, some of which are ongoing. Improvement in liver and lung function, and in 6-minute walk test have been reported. Efficient delivery of the vector to various tissues, and adequate expression of the introduced gene is being optimized.

The Shirols after Nidhi: 70 million Nidhis to care for

Way back in 2007 Prasanna had begun to appreciate the need and power of patient advocacy for rare disease. Gradually, as he understood the ecosystem more and more, he began to contribute meaningfully to the needs of rare disease patients across India. Today, Prasanna is one of the foremost pan-India champions of rare diseases. More about his work later.

From 2007 onwards Sharada had been the 24x7 caregiver for Nidhi. Her darling daughter was the focal point of her existence. Other than caregiving all her activities were related to rare diseases, disability, and patients’ needs under the banner of Inclusive India. Even the conversations with her husband always revolved around Nidhi. Without her daughter, Sharada was left, as though in a vacuum. The couple decided to start travelling frequently to repopulate their minds with new sights and sounds. Simultaneously they started thinking of more ways by which Sharada could contribute to the rare disease community with her vast experience of caregiving. There are an estimated 70-90 million rare disease patients in India. Today, Sharada speaks regularly to parents in distress, advising them about handling emergencies and answering their queries. Sharada has also completed her diploma in pharmacy and is now a certified pharmacist. She deals exclusively with rare disease drugs. The high margin of discount which they get from the drug companies is passed on to the patient, with only a nominal amount kept for their own operational cost. This model is already working for cystic fibrosis, with over 300 patients across India getting the drugs at much reduced cost. Sharada is working with companies to obtain clearances for more rare disease drugs.

Prasanna: the advocacy journey culminating in Organization of Rare Diseases India (ORDI)

Prasanna’s first exposure to patient-led advocacy happened in 2007 after he learnt about the new ERT drug for Pompe disease. The drug was available for patients abroad, but no one knew when, if ever, would this hugely expensive drug be available in India. It seemed like a distant dream. Then, one day, out of the blue Prasanna got a phone call from Mary, a Pompe disease patient from the Netherlands. She was a patient advocate working very actively with the International Pompe Association operating from the Netherlands and U.S.A. She had heard about Nidhi, and was calling Prasanna to assure him that they were working with Genzyme to see that children in India would get the ERT drug. Prasanna was in a daze. An unknown person, herself a patient of this debilitating disease, calling him with a dramatic assurance! And it was not a hollow assurance either. Sure enough, soon after Genzyme opened its doors in India Nidhi started receiving the drug free of cost under the charitable access programme. To Prasanna this was hard evidence of the sheer power of patient-led advocacy and he decided to make a plunge into it.

To begin with Prasanna started helping Genzyme India to find Pompe disease patients by approaching government hospitals and checking patient records. He started exploring ways of getting government funding to support the high cost of ERT drug. He also started connecting with other international rare disease groups like European Organization for Rare Diseases (Eurordis).

The turning point, which placed Prasanna on a firm footing for rare disease advocacy, came in 2009 when Genzyme sponsored him to attend the Asian Lysosomal Storage Disease (LSD) symposium in Taiwan. This turned out to be a goldmine. He learnt a lot and made many valuable contacts. The top clinical geneticists and paediatricians from India were attending the meeting. He met Dr. I.C. Verma, Dr. Madhulika Kabra, Dr. Ratna Puri, Dr. Meenakshi Bhat and discussed with them about connecting the Indian patients and families of all LSDs, including Pompe, all across India. He drew inspiration from the Taiwan Rare Disease Foundation who were actively engaged in rare disease awareness amongst medical fraternity, promoting new born screening, and providing patient support. Prasanna resolved to emulate their example once he returned home.

2009: The birth of Lysosomal Storage Disorders Support Society (LSDSS)

Under the leadership of Dr. I.C. Verma, Gangaram hospital, New Delhi was the major hub of rare genetic disease-related activities in India. They had a cohort of nine Gaucher disease (another LSD) patients who were receiving ERT from Genzyme. Dr. Verma’s group held periodic meetings with these parents who were mostly from Delhi. Prasanna attended their next meeting, and along with some of the active parents (which included Mr. Manjit Singh, now the President of LSDSS), they decided to register a society by the name LSDSS, using the Gangaram hospital as their address. Their immediate agenda was to increase public awareness of these rare diseases, and to approach government agencies to provide treatment for their children. The challenge was to find enough patients to justify a mega event that would catch the attention of doctors and government agencies.

February 28, 2010: The first International Rare Disease Day celebrated in India

In 2008 the European rare disease organization, Eurordis were the first to start observing the last day of February as Rare Disease Day to raise global awareness of rare diseases. Prasanna suggested that this would be a good date for them to launch their maiden event in 2010. The LSDSS group set to work, requesting doctors to share contact details of rare disease patients. Genzyme India, headed by Mr. Anil Raina, offered generous support. As many as 350 people from all over India attended the one-day event. Funds were raised to support the travel and stay of participants. The top specialists in clinical genetics attended the event. A multidisciplinary medical evaluation camp was also conducted to examine patients. In this positive atmosphere, a lot of parents came forward to share their stories. This caught the attention of mainstream media and they were interviewed by several TV channels. Doordarshan conducted a one-hour interview of the top rare disease doctors along with patient advocates like Prasanna and Manjit. From all counts the event was a resounding success and provided the perfect springboard for rare disease advocacy.

From then on, LSDSS celebrated every RD day with great fanfare in different cities, with celebrities as their mascots. In 2011 the event was held in Chennai, with the popular actor Karti Shivkumar as the star attraction. In 2012 the event was held in Mumbai with the popular singer Shaan gracing the occasion. In 2013 the scene again shifted to Delhi. This time the health secretary and the cricketing star Azharuddin were the draw. Obviously, the purpose of attracting mainstream media to report about rare diseases could not have been served better.

Catching the attention of government agencies and politicians

Government health agencies have their hands full trying to contain the ‘common’ life-threatening infectious diseases and other disorders where patient numbers are large. While they empathize with rare disease patients on an individual basis, getting them to make policies that would meaningfully change the ground reality for these patients, required strategies that Prasanna would gradually learn as he traversed this journey. He gratefully recalls the hand-holding he received from Archana Pande who was then working for Genzyme as a PR officer. She gave him useful tips about how to draft letters addressed to government officials, how to speak with MLAs and CMs to make an impression etc.

Along with LSDSS parents Prasanna started approaching various government agencies to draw their attention to rare diseases. They sought an appointment with the then ICMR director-general, Dr. V.M. Katoch. The result was the setting up of the first national task force for LSDs. Six referral centres were set up across the country which received funding to conduct free enzyme assays for diagnosis of LSDs. Early diagnosis is half the battle won, and this incentive was a game-changer.

Prasanna was always plagued with the question of long-term continuity of the compassionate use program. What if the programme stopped? Would the government pay for these drugs without which their children would not survive. In 2010, they obtained an appointment with the then Delhi CM, Mrs. Sheela Dikshit. She was deeply moved to see the plight of LSD children and gave financial approval to set up a corpus fund for obtaining ERT drugs. Unfortunately, soon after, there was a change in government and the initiative was lost. Such hurdles were to be more the rule than the exception in Prasanna’s engagement with government, but he took it all in its stride and looked for every small victory. Seeking appointments and meeting top officials was not translating into funding support for drugs, but at least it was sensitizing the concerned departments about RDs. Prasanna’s favourite motto says it all- ‘Disease may be rare but hope shouldn't be’.

2011-2014, Prasanna: Nudging the Karnataka state government into action

Health being a state subject, it made sense to approach individual state governments for funding support to procure RD drugs. Prasanna prepared a detailed note, with a dossier of Nidhi’s medical condition, and sent it to the Karnataka health secretary. He requested funding support for the ERT drug. The government machinery knows only too well how to exploit loopholes to spurn such audacious requests. The negative reply stated that there was no existing scheme to provide such support. In addition, they did not support patients being treated in private hospitals.

Dr. Meenakshi Bhat had been Prasanna’s guide ever since the Taiwan meeting. This time too she gave him some very practical suggestions. He should approach the government with a list of all Karnataka LSD patients. They should all have confirmed diagnosis from a government hospital. Prasanna set to work.

A major reason for not finding good numbers of RD patients in a populous country like ours is poor diagnostic facilities. While the situation has vastly improved today, a decade ago correct diagnosis was hard to come by for a category of rare disease like LSD. Nevertheless, Prasanna managed to connect with 45 patients across Karnataka. Dr. CN Sanjeeva at the government-run Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health provided the certified diagnosis. A large folder was prepared with details of all 45 patients and sent to the Chief Minister, Chief secretary, health minister, health secretary and all related departments like disability, women and child health, social justice etc. All of them replied saying that they had forwarded the file to the health department. Inundated with the same file from all sources, the health department did nudge a bit and agreed to meet Prasanna. But they were a hard nut to crack. Prasanna had to wait hours on end to have an audience with the health secretary. The response would be rude verbal abuse. A sample- “Did I give birth to your daughter that I have to provide her money for medicine?” But Prasanna was not the one to be dissuaded by such tactics. He would surface again and again. It reached a point when the moment he entered the health ministry office with a fresh letter the receptionist would shout for instructions- “The ventilator case has come again. Should I give acknowledgement for his letter?”

Finally, Prasanna reckoned after so many appeals he had a strong enough case to move the Courts. In 2014 he filed a case in the Karnataka High Court on behalf of 45 LSD patients of Karnataka. On the first hearing itself the honourable High Court gave the order to provide drug to the patients who were not receiving it under the compassionate use policy. The government was to release Rs. one crore for the treatment of 6-7 eligible patients in the group, but they were dragging their feet. During this period two of the children lost their lives. The money was finally released only after Prasanna threatened to file for contempt of Court. This became the first big victory for the rare disease community of India.

Simultaneously, the Delhi High Court was also moved on behalf of other rare disease patients by other patient groups, and the government was finally taking note. In 2017 the first Rare Disease Policy was formulated by the central government, which, not having been thought through fully, was replaced in 2021 by the present National Policy for Rare Diseases (NPRD). Although still not comprehensive enough, the NPRD, 2021 is a testament to the collective power of rare disease patient advocates, of whom Prasanna Shirol is a towering figure.

2014: The birth of Organization of Rare Diseases India (ORDI)

ORDI is one of the foremost ‘umbrella’ organizations of India which take under their wings all rare diseases instead of focusing on a particular RD. Prasanna’s name is synonymous with ORDI, being its co-founder and chief nurturer. The idea of ORDI first arose in his mind around 2013. By then Prasanna was a well-known figure in international RD circles, and was being invited to various RD advocacy meetings. As his exposure to a large number of different RDs and umbrella organizations increased, he decided to move beyond LSDs and work for advocacy of RDs in general. To move to this next level of advocacy, Prasanna resigned from his job to devote full-time effort for his advocacy work. There was a lot to be done. Already Prasanna was in touch with doctors treating RDs in 12 states of India where he was involved in conducting continuing medical education programs on RDs. He had now to cover more RDs and more states.

ORDI was officially launched from New Delhi in Feb 2014, with the primary goal to provide a better life for all people living with RDs in India. Their objectives include raising public awareness about RDs, lobbying with government agencies to formulate effective RD policies, connecting with patient organizations in India and abroad to be the voice of all RDs, to promote early diagnosis through new born screening, and research efforts to develop indigenous treatments. One of ORDI’s flagship programmes, ‘Race for 7’ (in support of 7,000 different known RDs), has been hugely successful to raise awareness about RDs. Every year, around Rare Disease day (last week of Feb), ORDI invites people to participate in a race to show their solidarity with RD patients. The race is organized in various cities across India. Other successful ventures of ORDI include running a helpline where RD patients and caregivers can get information and assistance; and organizing continuing medical education camps in various locations to raise awareness about RDs amongst medical practitioners. The Directors of ORDI are assisted in executing their programmes by a very dedicated and capable team of young professionals. For further details about ORDI, please visit their website https://ordindia.in/.

The man of perseverance Prasanna is today was shaped from early childhood when he saw his father fight for justice and endure hardships for seventeen long years, and finally emerge victorious. Prasanna has meticulously employed the management principles he learnt in business school to raise the bar in Indian rare disease advocacy. One must think big, and think smart, especially when the going is tough.

The statistic of an estimated 70-90 million RD patients in India has been used by Prasanna to draw attention to these diseases which are far from rare when considered in totality. The bulk of these patients reside in rural areas where health services and infrastructure are wanting. Prasanna feels he is destined to reach out to these communities. During the MBA programme the special paper he presented was on rural marketing and delivering services through nonprofit entities. Unbeknown to him, Fate was preparing him to take on these challenges and lead from the front.

Today, Sharada and Prasanna live fully in the world of rare diseases. Nidhi is physically gone but her presence pervades all their thoughts and actions. She is the force that leads them on.

References

-Naresh K. Meena and Nina Raben; Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1339; doi:10.3390/biom10091339

-Melani Solomon and Silvia Muro; Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.004

-Ankit K. Desai, Cindy Li, Amy S. Rosenberg, Priya S. Kishnani; Ann Transl Med 2019;7(13):285 |http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.05.27

-Angela L. Roger et al. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022; 22(9): 1117–1135; doi:10.1080/14712598.2022.2067476

Thanks for your share

Thank you for such a sensitively written article with such detailed information for us all.